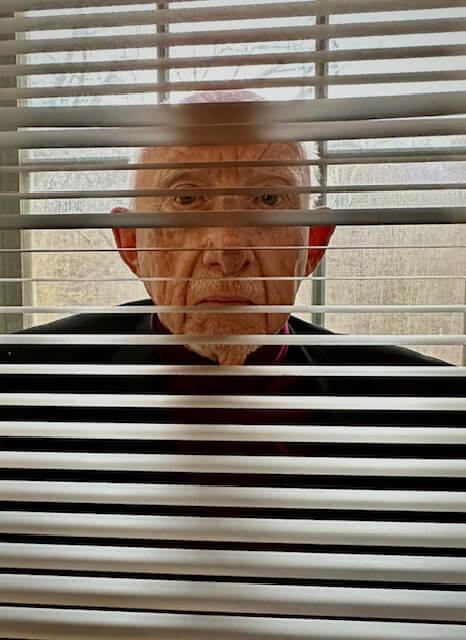

For me, the most remarkable thing about Facebook boss Mark Zuckerberg’s appearance at a Los Angeles court, to answer questions about the addictive aspects of social media, was that he was there at 8:30 a.m. wearing a suit.

Sarah Wynn-Williams, in her excellent book about Facebook, “Careless People: A Cautionary Tale of Power, Greed and Lost Idealism,” said Zuckerberg doesn’t see anyone before noon because he has to sleep, having been up most of the night.

This had Wynn-Williams, who rose to head Facebook’s international relations team, sometimes telling heads of state that they would have to wait for the great man to alight from his bed at noon or later.

Zuckerberg could be uninterested or uninformed about the country from which he was trying to get favors for Facebook, she wrote. As Facebook had electorates in its thrall, countries’ leaders were prepared to defer to the sleeping titan.

This doesn’t mean that Zuckerberg is evil, but it does point to enormous self-regard. His sleeping routine is a de facto declaration: I am so rich and so powerful that I can command world leaders to rearrange their schedules to accommodate mine. They did, according to Wynn-Williams.

While the venerable observation by Lord Acton in 1887 that “power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely” is nearly always directed at politicians and autocrats, it is as true for billionaires and their companies.

More so with the tech gargantuans who are a force in the financial markets and politics, and will control much of the future if their investments in artificial intelligence pay off. Among them are Meta (Facebook), Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, Nvidia, Microsoft, Tesla, Anthropic and OpenAI.

Another point Wynn-Williams made in her book is that most of the heads of state whom Zuckerberg treated with minimal respect won’t be in power in 10 years, but Zuckerberg, who is 41, may be around for half a century. The long game is his, along with his colleague-companies and their CEOs, especially when they own a commanding amount of the stock, like Tesla’s Elon Musk.

The effect of Big Tech as a lobbying force is apparent: Any CEO has access to the White House and is, in turn, cultivated by it. Congress has a permanent welcome mat out to Big Tech lobbyists and their campaign contributions.

A more damaging impact might be what Big Tech does to new tech.

The biggies buy up every startup that looks as though it might become a mega company. All of the Big Tech companies are conglomerates, and history has shown that conglomerates discard unprofitable enterprises and favor the cash cows. Tech autocracy is no kinder than any other autocracy.

Startups are what keep America ahead of the world in tech, and they are keenly watched for any sign that they may grow into another agent of change. Whereas at the beginning of the tech boom, successful startups headed for an initial public offering, and now they calculate from the get-go which behemoth tech company will buy them. The circle is closed.

The big get bigger, and the startup is absorbed into a giant organization, where it might prosper or whither. Either way, it is out of reach, including regulatory reach. It is in the castle walls.

As we see with the fate of CBS and The Washington Post, Big Tech can play havoc with the media and our right to know what is going on. The money is so large that it is almost impossible for politicians not to seek the favor of the mighty techs and their Vesuvian cash flow.

The obverse of that is what they might do if they overreach, as they may be doing now with AI investments, and bring down the stock market.

Big Tech has showered us with wonders that have made life easier and fun, but there is a price. The price is that we have handed the future to a group of companies that, understandably, are interested in self-preservation first, as with all autocracy.