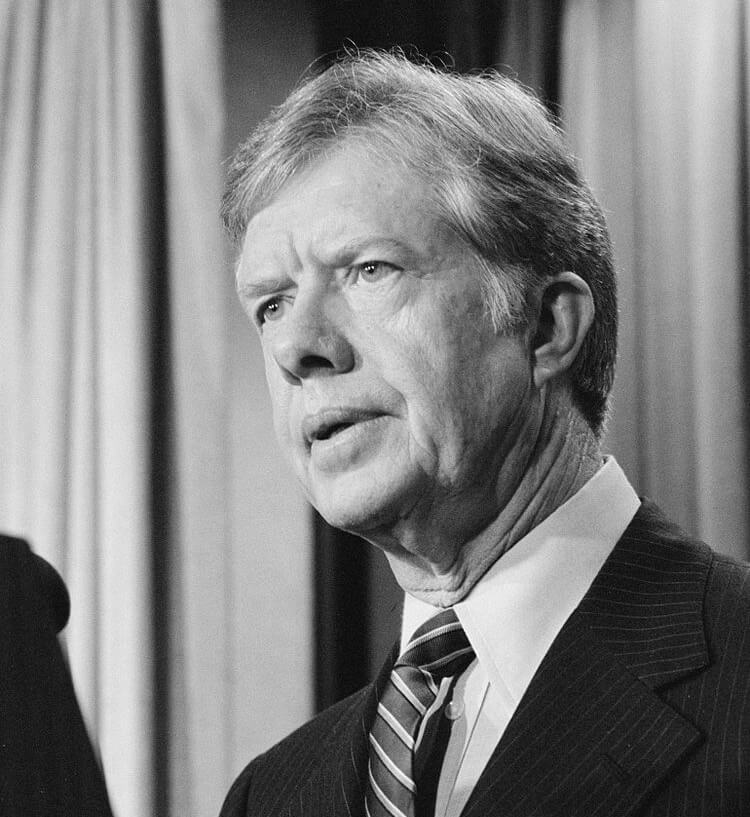

The ghost of Jimmy Carter may be stalking energy policy in the White House and the Department of Energy.

In the Carter years, the struggle was for nuclear power. Today, it is for natural gas and America’s booming liquefied natural gas future.

The decisions that Carter took during his presidency are still felt. Carter believed that nuclear energy was the resource of last resort. Although he didn’t overtly oppose it, he did damn it with faint praise. Carter and the environmental movement of the time advocated for coal.

The first secretary of energy, James Schlesinger, a close friend of mine, struggled to keep nuclear alive. But he had to accept the reprocessing ban and the cancellation of the fast breeder reactor program with a demonstration reactor in Clinch River, Tennessee. Breeder reactors are a way of burning nuclear waste.

More important, Carter, a nuclear engineer, believed the reprocessing of nuclear fuel — then an established expectation — would lead to global proliferation. He thought if we put a stop to reprocessing at home, it would curtail proliferation abroad. Reprocessing saves up to 97 percent of the uranium that hasn’t been burned up the first time, but the downside is that it frees bomb-grade plutonium.

Rather than chastening the world, Carter essentially broke the world monopoly on nuclear energy enjoyed — outside of the Soviet bloc — by the United States. Going forward, we weren’t seen as a reliable supplier.

Now, the Biden administration is weighing a move that will curtail the growth in natural gas exports, costing untold wealth to America and weakening its position as a stable, global supplier of liquified natural gas. It is a commodity in great demand in Europe and Asia and pits the United States against Russia as a supplier.

What it won’t do is curtail so much as 1 cubic foot of gas consumption anywhere outside of the United States.

The argument against gas is that it is a fossil fuel and fossil fuels contribute to global warming. But gas is the most benign of the fossil fuels, and it beats burning coal or oil hands down. Also, technology is on the way to capture the carbon in natural gas at the point of use.

But some environmentalists — duplicating the folly of environmentalism in the Carter administration — are out to frustrate the production, transport and export of LNG in the belief that this will help save the environment.

The issue the White House and the Energy Department are debating is whether the department should permit a large, proposed LNG export terminal in Louisiana at Calcasieu Pass, known as CP2, and 16 other applications for LNG export terminals.

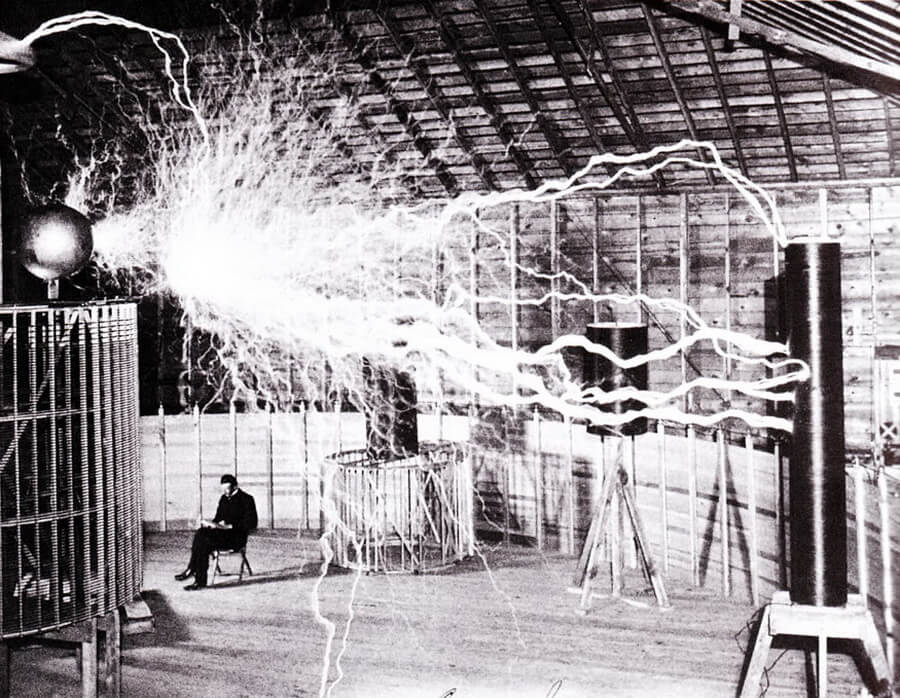

The recent history of U.S. natural gas and LNG has been an industrial and scientific success: a very American story of can-do.

At a press conference in 1977, the then-deputy secretary of energy, Jack O’Leary, declared natural gas to be a depleted resource. He told a reporter not to ask about it anymore because it wasn’t in play.

Deregulation and technology, much of it developed by the U.S. government in conjunction with visionary George Mitchell and his company, Mitchell Energy, upended that. The drilling of horizontal wells using 3D seismic data, a new drill bit, and better fracking with an improved fracking liquid changed everything. Add to that a better turbine, developed from aircraft engines, and a new age of gas abundance arrived.

Now, the United States is the largest exporter of LNG, and it has become an important tool in U.S. diplomacy. It was American LNG that was rushed to Europe to replace Russian gas after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

In conversations with European gas companies, I am told they look to the United States for market stability and reliability.

Globally, gas is a replacement fuel for coal, sometimes oil, and it is essential for warming homes in Europe. There is no alternative.

The idea of curbing LNG exports, advanced by the left wing of the Democratic Party and their environmental allies, won’t keep greenhouse gases from the environment. It will simply hand the market to other producers like Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.

To take up arms against yourself, Carter-like, is a flawed strategy.