I’ve been here before. I’ve heard this din at another time. I’m writing about the cacophony of opinions about global warming and climate change.

In the winter of 1973, the Arab oil embargo unleashed a global energy crisis. Times were grim. The predictions were grimmer: We’d never again lead the lives we had led — energy shortage would be the permanent lot of the world.

The Economist said the Saudi Arabian oil minister, Sheik Ahmad Zaki Yamani, was the most important man in the world. It was right: Saudi Arabia sat on the world’s largest proven oil reserves.

Then as now, everyone had an answer. The 1974 World Energy Congress in Detroit, organized by the U.S. Energy Association, and addressed by President Gerald Ford, was the equivalent in its day to COP26, the UN Climate Change Conference which has just concluded in Glasgow, Scotland.

Everyone had an answer, instant expertise flowered. The Aspen Institute, at one of its meetings, held in Maryland instead of Colorado to save energy, contemplated how the United States would survive with a negative growth rate of 23 percent. Civilization, as we had known it, was going to fail. Sound familiar?

The finger-pointing was on an industrial scale: Motor City was to blame and the oil companies were to blame; they had misled us. The government was to blame in every way.

Conspiracy theories abounded. Ralph Nader told me there was plenty of energy, and the oil companies knew where it was. Many believed that there were phantom tankers offshore, waiting for the price to rise.

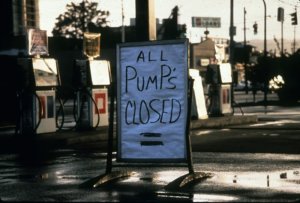

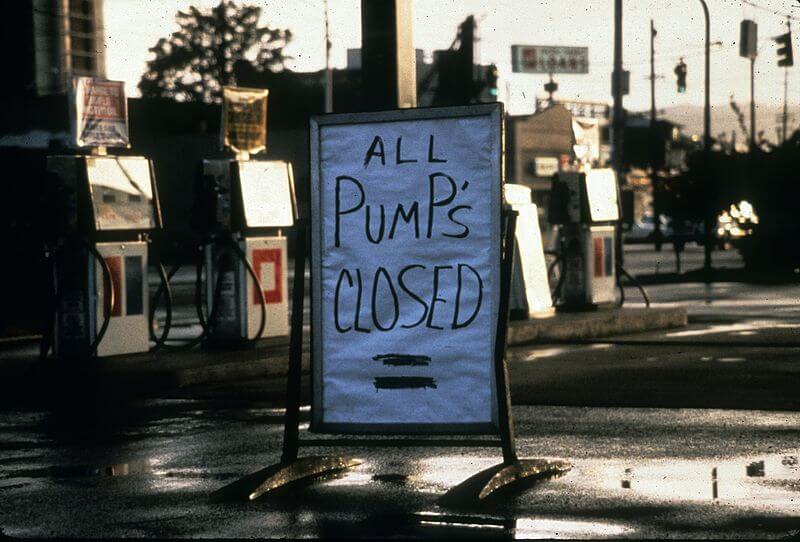

Across America, there were lines at gas stations. London was on a three-day work week with candles and lanterns in shops.

In February 1973, I had started what became The Energy Daily and was in the thick of it: the madness, the panic — and the solutions.

What we were faced with back then was what appeared to be a limited resource base which the world was burning up at a frightening rate. Oil would run out and natural gas, we were told, was already a depleted resource. Finished.

The energy crisis was real, but so was the nonsense — limitless, in fact.

It took two decades, but economic incentive in the form of new oil drilling, especially in the southern hemisphere, good policy, like deregulating natural gas, and technology, much of it coming from the national laboratories, unleashed an era of plenty. The big breakthrough was horizontal drilling which led to fracking and abundance.

I suspect if we can get it right, a similar combination of good economics, sound policy, and technology will deliver us and the world from the impending climate disaster.

The beginning isn’t auspicious, but neither was it back in the energy crisis. The Department of Energy is going through what I think of as scattering fairy dust on every supplicant who says he or she can help. On Nov. 1, DOE issued a press release which pretty well explains fairy dusting: a little money to a lot of entities, from great industrial companies to universities. Never enough money to really do anything, but enough to keep the beavers beavering.

That isn’t the way out.

The way out, based on what we have on the drawing board today, is for the government to get behind a few options. These are storage, which would make wind and solar more useful; capture and storage of carbon released during combustion; and a robust turn to nuclear power.

All this would come together efficiently and quickly with a no-exceptions carbon tax. Republicans will diss this tax, but it is the equitable thing to do.

Nuclear power deserves a caveat. It is unique in its relation to the government, which should acknowledge this and act accordingly.

The government is responsible for nuclear safety, nonproliferation, and waste disposal. It might as well have the vendors build a series of reactors at government sites, sell the power to the electric utilities, and eventually transfer plant ownership to them.

The government has some things that it alone is able to do. Reviving nuclear power is one.

The energy crisis was solved because it had to be solved. The climate-change crisis, too, must be solved.