America has your back. That has been the message of U.S. foreign policy to the world’s vulnerable since the end of World War II.

That sense that America is behind you was a message for Europe against the threat of the Soviet Union and has been the implicit message for all threatened by authoritarian expansionism.

From the sophisticated in Western Europe to the struggling masses worldwide, America has always been there to help. Its mission has been to serve and, in its serving, to promote the American brand — freedom, democracy, capitalism, human rights — and to keep America a revered and special place.

America was there to arbitrate an end to civil war, to rush in with aid after a natural disaster, to provide food during a famine and medical assistance during an infectious disease outbreak. America was there with an open heart and open hand.

If you want to look at this in a transactional way, which is the currency of today, we gave but we got back. The ledger is balanced. For example, we sent forth America’s food surplus to where it was needed, from Pakistan to Ethiopia, and we opened markets to our farmers.

The world’s needs established a symbiotic relationship in which we gained reverence and prestige, and our values were exported and sometimes adopted.

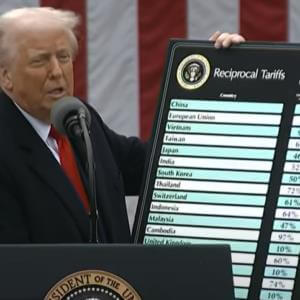

President Trump has characterized us as victims of a venal world that has pillaged our goodwill, stolen our manufacturing and exploited our market. The fact is that when Trump took office in January, the United States had the best-performing economy in the world, and its citizens enjoyed the products of the world at reasonable prices. Inflation was a problem, but it was beginning to come down — and it wasn’t as persistent as it had been in Britain, for example.

Trump has painted a picture of a world where our manufacturing was somehow shanghaied and carried in the depth of night to Asia.

In fact, American businesses, big and small, sought out Asian manufacturing to avail themselves of cheap but talented labor, low regulation, and a union-free environment.

Businesses will always go where the ecosystem favors them. The business ecosystem offshore was as irresistible to us as it was to a tranche of European manufacturing.

The move to Asia hollowed out the old manufacturing centers of the Midwest and New England, but unemployment has remained low. Some industries, including farming, food processing and manufacturing, suffer labor shortages.

We need manufacturing that supports national security. That includes chips, heavy electrical equipment and other essential infrastructure goods. It doesn’t include a lot of consumer goods, from clothing to toys.

Former California Sen. S.I. Hayakawa, a Republican and a semanticist, said you couldn’t come up with the correct answer if your input was wrong, “no matter how hard you think.” Trump’s thinking about the world seems to be input-challenged.

The world isn’t changing only in how Trump has ordained but in other fundamental ones. Manufacturing in just five years will be very different. Artificial intelligence will be on the factory floor, in the planning and sales offices, and it will boost productivity. However, it won’t add jobs and probably will subtract them.

Trump would like to build a Fortress America with all that will involve, including higher prices and uncompetitive factories. While not undermining our position as the benefactor to the world, a better approach might be to build up North America and welcome Canada and Mexico into an even closer relationship. Canada shares much of our culture, is rich in raw materials, and has been an exemplary neighbor. Mexico is a treasure trove of talent and labor.

Rather than threatening Canada and belittling Mexico, a possible future lies in a collaborative relationship with our neighbors.

Meanwhile, Canada is looking for markets to the East and the West. Mexico, which is building a coast-to-coast railway to compete with the Panama Canal, is staking much on its new trade deal with the European Union.

Trump has sundered old relationships and old views of what is America’s place in the world order. No longer does the world have America at its back.

This is a time of choice: The Ugly American or the Great Neighbor.