On Dec. 13, I will receive an award and give a dinner talk at the National Press Club in Washington, recognizing my 68 years as a journalist and my 58 years as a member of the club.

This recognition is from a club subsection, known as the Owls. Silver Owls are those who have roosted at the club for 25 years or longer; Golden Owls, 50 years or more; and Platinum Owls, 60 years or longer.

You may think the hot type days in newspapers are long past, along with black-and-white television. They may be, but the denizens of that time live on — or some of us do.

We will crowd the storied National Press Club ballroom to raise a glass to the time when headlines had to fit to an exact letter count, when wire services moved the news over teleprinters at 64 words a minute: It could be the biggest story in the world, but it would be moved slower than the speed of reading.

The trick was to break the news into very short takes and move it on several printers. The principal teleprinter of the news services, UPI, AP and Reuters, was equipped with a “bulletin” bell which rang when the biggest news, like an assassination, broke.

In the composing room, where “metal” (you dared not call it lead, even though it was predominantly lead with some tin and antimony) was cast into type and into “furniture,” the rules and the spacing bars that went between the lines of type, craftsmanship ruled.

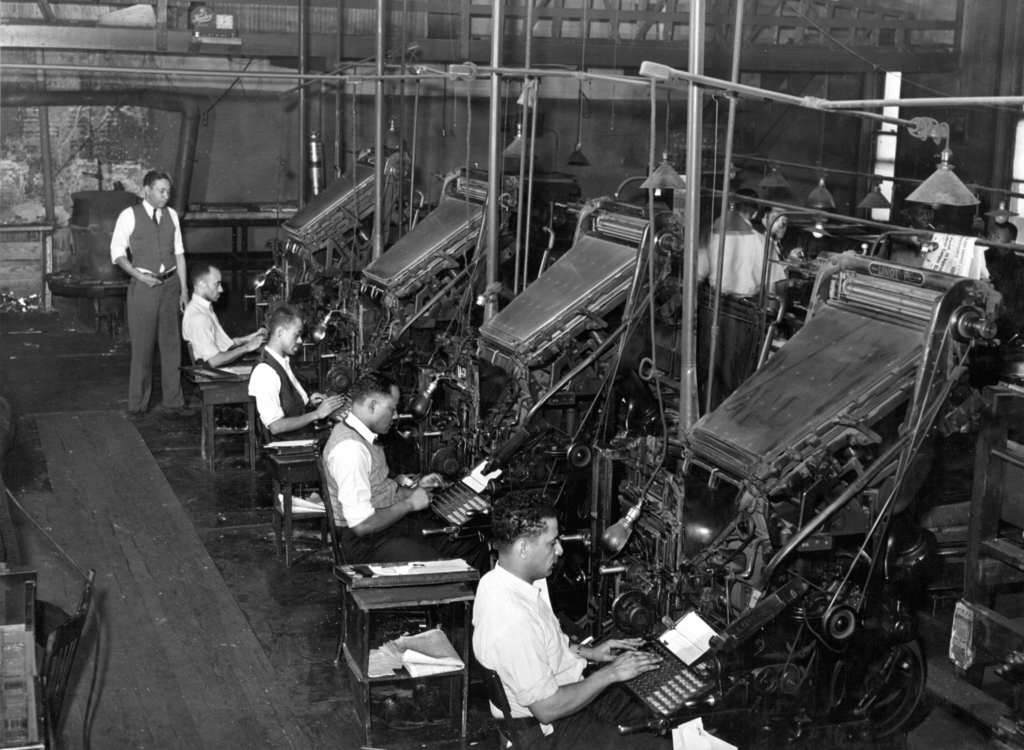

At one side of that great hive were the Linotype machines, operated by skilled people who could change fonts and type sizes by levering up or down the brass boxes that contained the dies of the type. They were the kings and queens of that art, secure and unflappable. Each Linotype machine contained a thousand parts, according to the Museum of Printing in Haverhill, Massachusetts.

In a rush the printers (note to laymen: printers set and handled the type), the people who ran the presses were pressmen, could assemble a whole page in minutes. If news had broken or, heaven forfend, a page had been “pied” (dropped, type all over the floor) then everything had to be reset and assembled.

Television — when I first worked in it in London, in the days of black-and-white — had its own foibles and culture, and the love of a glass of something.

The equivalent of the printers were the film editors, craftsmen and women all. One of the most skilled, who had had a long career in movies, would entertain us at the in-house bar in the BBC news studios in North London, by swinging a full pint mug of beer over his head without spilling any.

With the same dedication, he would slice and link the celluloid on deadline. He was the man who would save the day, especially if film came in late. Tape was in its infancy.

In the newsrooms on newspapers, tactically just one floor above the composing room, there were the journalists — that irregular army of misfits and egotists who made up a subculture unique to themselves. In Britain, they were referred to somewhere as “the shabby people who smell of drink.” That was true of journalists all over the world in those days. I can attest, bear witness. I was there.

Among the journalists, writers, editors, cartoonists, columnists, photographers, designers, secretaries and librarians were a cast of characters that was almost always the same in every newsroom, print or television. There was the Beau Brummell, the lover, the agony aunt, the gossip, the budding author, and the drunk (who wrote better than anyone else and was tolerated because of that). Then sadly, the gambler.

It seemed to me the drinkers had camaraderie and laughter, the gamblers just losses.

That began to change about 1970, when I was at The Washington Post. There were still drinkers who did the deed at the New York Lounge, a hole in the wall next to the more famous but less used by us Post Pub. But the drinking was definitely down. Among the younger members of the staff, pot was the recreational drug. The older ones still favored a drink.

In London, the big newspapers and the BBC maintained bars in their offices. It made it easy to find people when they were needed.

At the venerable New York Herald Tribune after the first edition closed at 7:30 p.m., the entire editorial staff, it seemed, went downstairs and around the block to the Artist (cq) and Writers, also called Bleaks. It wasn’t known for the quality of its carbonated water, unless that was mixed with something brown.

At the Baltimore News-American, there was a secret route through the mechanical departments, enabling thirsty scribblers to reach the nearest bar undetected.

At the Washington Daily News, which belonged to the Scripps Howard chain of newspapers, the editor was known to favor the nearest bar, an Irish establishment called Matt Kane’s.

At the National Press Club celebration, we will raise one to the days of wine and roses, great stories and wordsmithing, and the fabulous adventure of it — the bad food, terrible hours, poor pay, long stakeouts, days far from home, and always, as my late first wife and great journalist, Doreen King, said, “the inner core of panic” about getting things right. We do care, more than our readers and viewers know.

There is, for all of its tribulations, no greater, more exciting place to be than in a newsroom as big news is breaking.

You are there, inside history.