Barry Worthington, who was executive director of the U.S. Energy Association for 31 years, died prematurely on Aug. 14, 2020. This is a remembrance of him, a dear friend, which I wrote at the time.

Barry Worthington was the most extraordinary ordinary man. Unpretentious, self-effacing, decent to the extreme, casual, and abundantly capable. He left a mark on electric utilities worldwide; and here, in the United States, on hundreds of energy denizens from senators to cabinet secretaries, and CEOs of companies crammed into the Fortune 500. He was, simply, exemplary — at once everyman and unique.

He stood on more podiums than many political candidates and delivered profound speeches in a conversational, clubby way. He walked with potentates and political savants from across the world and talked with them unaffectedly, as though he was leaning over a neighbor’s fence.

Barry’s travels were the stuff of awe and legend: off to Beijing, Dubai or Rio de Janeiro today, and back tomorrow. If there were a prize for speed of travel turnaround, Barry would have won it over and over.

He told me that he had promised his wife Louise, a school principal, he would always get back as fast as possible. I think it was otherwise: I think home was where Barry’s heart was and he would rather be home in Laytonsville, Maryland than dining in Paris or sightseeing in Patagonia. If he had a place he preferred more than Laytonsville, it was the family condominium in Rehoboth Beach, Delaware.

Barry, for all the travel and international importance, was quintessentially a family man. He, Louise, Barry and Kerry, his now adult children, loved doing things together, quite simple, very American things like summering at the beach, going to Hard Rock Cafés, and visiting Disney theme parks.

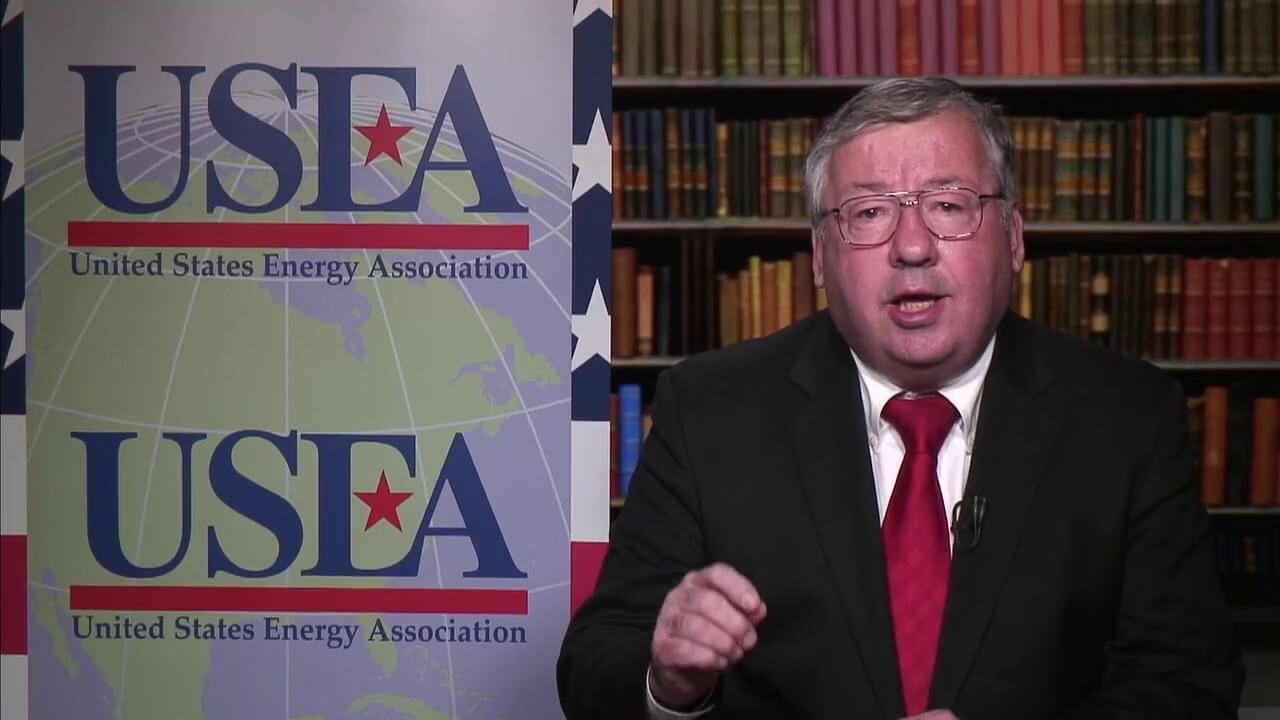

He was, for 31 years until his so-untimely death at age 66, executive director of the United States Energy Association. Under his gentle direction, the USEA grew from a moribund organization on a sharp downward trajectory to a $10-million-a-year, globe-circling player.

The USEA is a nonpartisan, non-lobbying organization, dating back to 1935, that promotes all forms of energy, based on the fundamental creed that energy is good for people. As its executive director, Barry was good for people, too.

Barry was educated at Penn State University and the University of Houston. He sought a career in energy at a time when the energy crisis appeared as though it would last forever and bend the future.

Houston Power & Lighting Company hired Barry as a trainee executive. He caught the eye of its legendary chairman, Don D. Jordan, and the two kept in touch. Barry often quoted Jordan in conversation.

Barry was offered a job with the nonprofit Thomas Alva Edison Institute. “I took it because it was twice the pay, and we were young and broke,” Barry told me.

The institute was foundering, and Barry accepted an offer to head the USEA which was itself a financial basket case. It had made a lot of money in 1974, when it hosted the World Energy Conference in Detroit, but that windfall was dwindling when Barry arrived. “It had expenses of $250,000 a year and income of $200,000,” Barry told me at lunch last January.

Something had to be done and quiet, unassuming Barry was the man to do it.

There was no way the USEA’s modest dues structure would support a revival. Products and services had to be added. Barry increased the number of revenue meetings, briefings and events, and boosted the role of industry briefings. As the publisher and editor in chief of The Energy Daily, I was able to introduce media breakfasts at the USEA.

Barry increased the usefulness of the USEA to its members. Although it had a special relationship with electricity, oil and natural gas companies found its services and contact matrix useful. The USEA’s work on carbon capture, utilization and storage has been pioneering.

When Barry brought in the United States Agency for International Development, the USEA found an unexpected mission: It began creative and cost-effective collaborations, pairing American electric utilities with those in the former Soviet Union to teach them best practices and establish a commercial basis. Sometimes these have included oil companies, but the bulk of the 80 “partnerships” have been in electricity and ranged from ratemaking to plant operation to fuel optimization. In eastern Europe, the first measure was to boost the cycles from 48.6 to conform with the western European standard of 50.

Today, these partnerships are a brilliant feature of foreign policy and have extended to South Asia and Africa.

A friend to many, Barry Worthington, has left us, but his light is not extinguished: It shines brightly across the world and in the hearts of those of us lucky to have known him. I was so favored for more than 30 years.