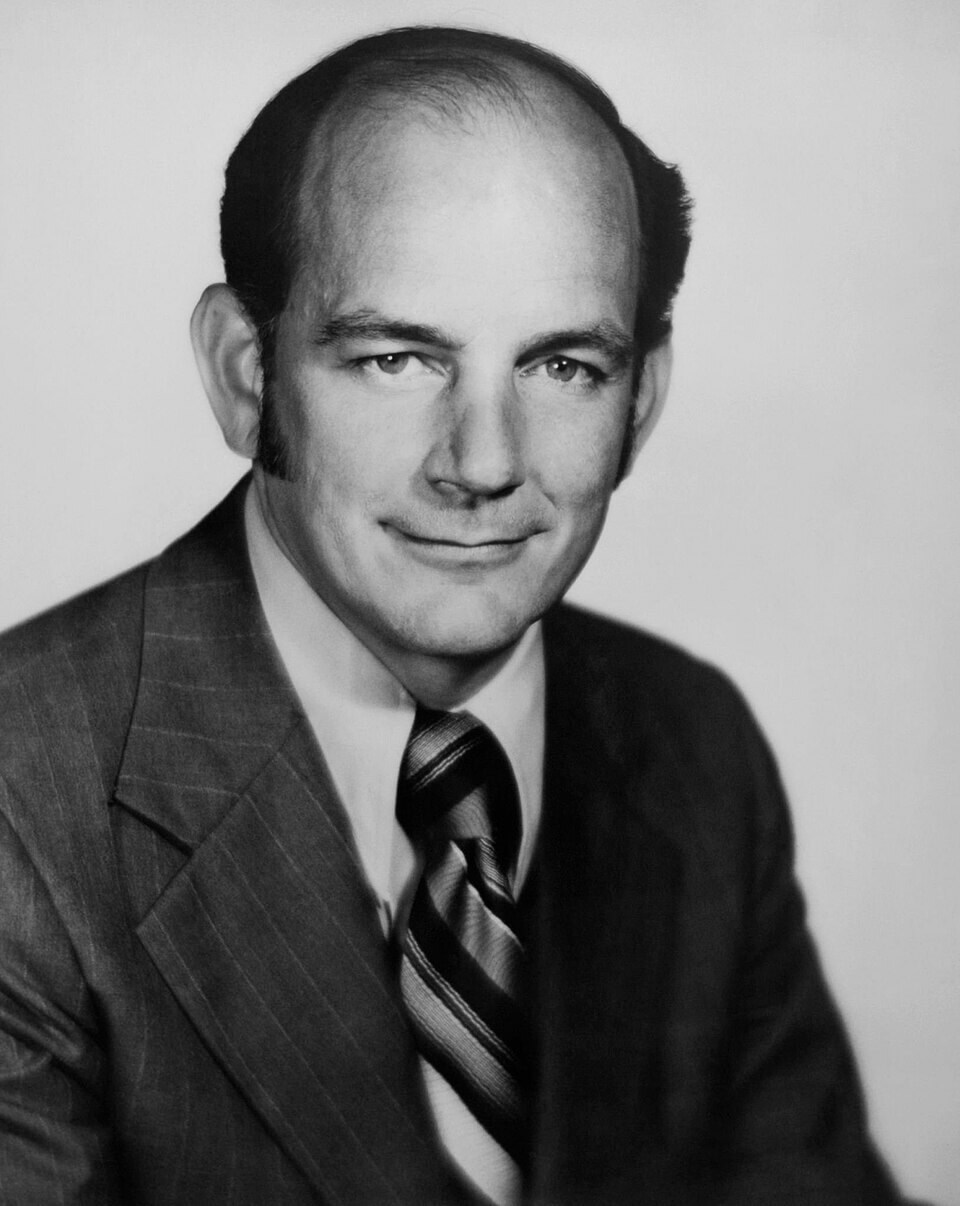

Anyone wondering about a career as a U.S. senator might want to study the life and times of Sen. J. Bennett Johnston (D-La.), who died March 25 at the age of 92. To me, he embodied the best of the Senate that was.

Johnston was both a patriotic American and a loyalist to the state that sent him to Congress. He also was bipartisan, curious and totally on top of his subject. His legislative milestones endure, from natural gas and oil deregulation to the electricity and environmental structure of today.

Johnston was an exemplar of the art of the Senate, when it was correctly known as the world’s greatest deliberative body. He was chairman of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee and, as such, was a major player in the shaping of energy and environmental policy.

He was a Democrat who worked across the aisle. Oddly, his most contentious relationship might have been that with President Jimmy Carter. They clashed over a water project on the Red River in Louisiana: Carter thought it was too expensive, but Johnston argued that it was needed. He admired President Bill Clinton for his brilliance.

In the aftermath of the Three Mile Island accident, he worked with President Ronald Reagan to establish the Institute for Nuclear Power Operations to save nuclear power from those who wanted to eliminate it.

Like other distinguished chairmen, Johnston recognized two fealties: to his state and to the nation.

I watched Johnston all his years as Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee chairman, and I came to revere and admire him as a great gentleman, a great patriot and a great senator.

Johnston was neither flashy, nor loud, but he was effective. The New York Times said of him that he was a notable exception, compared with the noisy and controversial political heritage of Louisiana, which included such notables as Huey and Earl Long and Edwin Edwards. Johnston was instead “a quiet intellectual with finely honed political judgments who grasped the technical intricacies of energy exploration and production and could also lucidly discuss astrophysics, subatomic particles and tennis serves.”

Thomas Kuhn, a former longtime president of the Edison Electric Institute, said Johnston had a lasting impact on environmental and energy policy during his 24 years in Congress with the Clean Air Act of 1990 and the Energy Policy Act of 1992.

When the Energy Policy Act was working its way through Congress, I saw Johnston at work up close. He invited me, as the founder and publisher of The Energy Daily, and Paul Gigot, then a Washington columnist for The Wall Street Journal and later its editorial page editor, to lunch in a small private dining room in the Senate.

Johnston was low-key yet forceful in seeking our support for the bill. I asked him, “Who is carrying your water on this one?” He responded in an endearing and lonesome way, “I’m afraid I am.” And carry it he did until it became law.

On another occasion, when President George H.W. Bush’s nomination of Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court was bogged down with Anita Hill’s allegations of impropriety by the nominee, Johnston told me, “I’m going to vote for him. I think when he looks in the mirror in the morning, he will see a black face and he will do the right things.” Maybe not Johnston’s best call.

While Kuhn may have met Johnston as a lobbyist, they became close friends and tennis partners. Kuhn told me Johnston was so passionate about tennis that he had a court built atop the Senate Dirksen Office Building. Among others, he would play tennis there with fellow Louisiana Sen. John Breaux.

Johnston was also passionate about Tabasco sauce and carried a bottle with him at all times.

Kuhn remembered this about his friend, “He was well-liked by everyone and had a great sense of humor. And he got things done on a bipartisan basis — a skill that is sorely missed in today’s Washington.”