The Sahara has a lot of land and a lot of sun, making it an appealing place to site massive solar generating stations, and the Kingdom of Morocco is doing just that.

Add substantial wind resources inland and on the coast and Morocco looks set to fulfill its declared intention of not only satisfying its own demands, but also becoming a regional exporter to North Africa and Europe.

It has a total installed generating capacity of about 11,000 MW, 4,030 MW of which is renewables. An additional 4,516 MW of renewables is under construction or planned.

King Mohammed VI, who has ruled the country for 23 years, has been a strong advocate for solar and other renewables. He is, you might say, a new kind of sun king.

The North African country hopes that it will inspire many countries to switch from fossil fuels to renewables. Leila Benali, the dynamic minister of energy transition and sustainable development, told me in an interview on Zoom that she wants Morocco to be “a destination for renewable energy.”

In due course, according to Benali, Morocco could export more of its power from renewables to Spain, Portugal, and even the United Kingdom. Currently, there are two electricity interconnections with Europe and a third is planned. The capacity of the interconnections is 1,400 MW and power flows both ways, depending on generating and market conditions in Europe and M0rocco. “Sometimes we are the only African country importing a commodity,” Benali joked.

If Morocco is to serve the UK, an additional interconnection would be needed, she said. Morocco already is interconnected to Algeria, Egypt, and Libya.

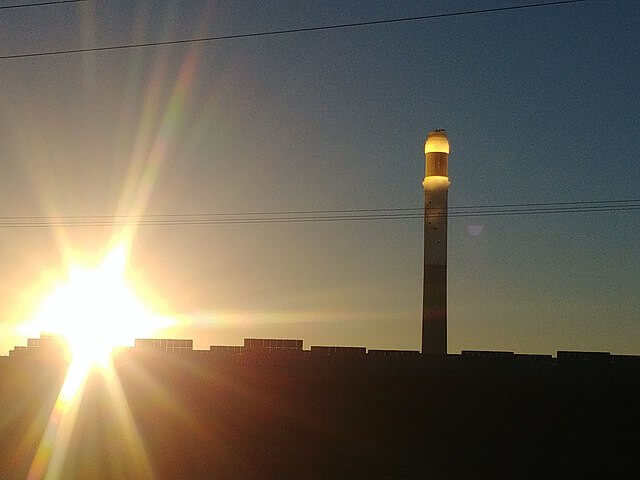

Once completed, the Noor Ouarzazate complex will be one of the largest solar power generating facilities in the world, covering more than 6,000 acres of desert. At present, the complex consists of three separate but co-located power stations, known as Noor I (160 MW), Noor II (200 MW), and Noor III (150 MW). A fourth station, Noor IV (72 MW), is planned.

The Moroccans are championing concentrated solar power (CSP), which has largely fallen by the way in the United States and Europe as photovoltaic (PV) cells have become very inexpensive. But CSP’s great advantage is that it has the ability to store energy and, therefore, to extend the availability of power. Noor I has 3 hours of storage capacity, Noor II and III have 7 hours each.

In the aftermath of the energy crisis of 1973, CSP technology held out major promise in the United States. Mirrors concentrate heat from these collectors to a boiler which heats water, for example, to 550 degrees Centigrade. The resulting steam generates the electricity through a turbine.

Rather than contributing to the infamous “duck curve,” where too much power is generated during the day and none during peak hours early in the morning and after the sun sets at night, CSP can cover those peaks. Surplus heat is stored in molten salt and used when needed either for electricity generation or other purposes. Benali told me she hopes that stored solar heat can be used for hydrogen production or desalination.

There have been a number of successful CSP installations in the United States, the largest of which is the 250 MW Solana plant in Gila Bend, Arizona. It has operated since 2013 on the APS system. CSP technology is also used in Israel, Spain, and other hot, sunny countries.

CSP has two downsides, cost and water availability, but abundant sunshine moderates the cost. You must build two systems: the collectors and the generator. By contrast, PV produces electricity directly. In a CSP plant, as with any other thermal power plant, water is needed for cooling and to wash down the collectors. The Noor facility is pumping water from a reservoir to meet its needs.

There are two CSP technologies and Morocco is employing both of them. One uses parabolic mirrors to direct the heat onto a pipe which carries a conduction fluid to the power plant. The other is the so-called power tower system. With this, sun-following mirrors, called heliostats, direct the sun to a collector at the top of a tower. Noor I and II are using parabolic collectors, and Noor 3 is using heliostats surrounding a tower which rises more than 800 feet.

Noor IV will be different: It will employ conventional PV cells. Benali told me, “We are ecumenical about renewable technology.”

She is proud of the huge projects as well as localized ones, including rooftop solar. She said the Moroccan administration is committed to bringing electricity to 100 percent of the population, from 99.4 percent today. The administration, she said, wants “every school, mosque, and home to have electricity” and if the last-mile cost is too high, they will employ microgrids.

According to Benali’s office, the capital cost of the solar projects has reached $5.2 billion. The ministry emphasized that Noor is far from the only development. It stated that 52 renewable projects are in operation, and 59 are under construction or planned.

Benali took office in October 2021, after a distinguished international career that included working for Schlumberger, Aramco, and Cambridge Energy Research Associates.

She has a splendid academic resume – holding degrees in engineering, economics, and political science — and a splendid sense of humor. When I asked her how she learned her flawless English, she told me she watched MTV as a child. The characters on her favorite show, “Beavis and Butt-Head,” never spoke with such easy articulateness.

This article was originally published on Forbes.com on Aug. 1, 2022.

Follow

Follow

Leave a Reply