The Mound Builders of Georgia

The Ocmulgee Earth Lodge’s doorway. Credit: Linda Gasparello.

On a January day at the Ocmulgee National Monument in Macon, Ga., a hiker ambles up the Great Temple Mound, a flat-topped, earthen ceremonial structure built by the Mississippians around 900-1100 AD. Just as the Scottish explorer Joseph Thompson described Mt. Kilimanjaro in 1887, the mound is “entirely suggestive of solidity and repose, of serene majesty asleep.”

Macon lawyer Christopher Smith, a tall mound of a man, guided my husband Llewellyn King and I through the national park, which preserves an area that has been inhabited by humans since the Ice Age (before 9,000 BC).

From the Visitors Center, we walked across a wooden bridge over a stream flanked by spindly Georgia pines and up a hill path to the Earth Lodge, which was probably a meeting place for the town’s political and religious leaders.

Crouching, we entered the grass-covered lodge through an opening buttressed with thick wooden planks. Bent at our waists, we walked through a narrow hall with woven reed walls into the reconstructed council chamber of the Mississippians.

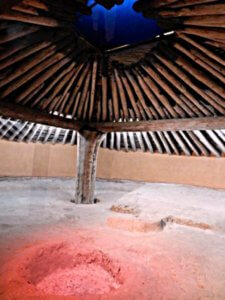

The circular chamber incorporates and protects the original clay floor, which is about 1,000 years old. There is a round fire pit and a raised platform in the shape of a large bird, where the chiefs or high priests sat. The chamber’s wood-beamed ceiling and clay walls give it the look and feel of a Tudor chapel.

The Tudor chapel-like earth lodge chamber. Credit: Linda Gasparello.

“The site of Ocmulgee is synonymous with Georgia and Southeastern archeology. During the 1930s, it was a training ground for a whole generation of American archeologists, some of whom later became the ‘fathers’ of modern American archeology,” according to the National Park Service.

The history of the park, from its inception as a Depression-era works project through to World War II, is intertwined with archaeological project management on a grand scale by the Smithsonian Institution, various federal relief agencies (the Works Project Administration, Civilian Conservation Corps, and the Federal Emergency Relief Agency) and the National Park Service.

From 1933 to 1942 as many as 1,200 people excavated the site under the direction of Arthur R. Kelly, a Harvard-trained archaeologist working for the Smithsonian, and built the Visitors Center, which contains beautifully crafted dioramas of human habitation of the area from 10,000 BCE to the early 1700s. The 702-acre site was designated a National Monument in 1936; it is now a national park.

We toured Ocmulgee a day before its closure on Jan. 20, due to the government shutdown. That day, the national park posted a message on its Facebook page that the Visitors Center and Earth Lodge would be closed during the shutdown, but the roads, trails and outside grounds would be open as usual, daily from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Dee Shannon Garrison left this comment on the page, “Stupid congress critters. Ain’t happy unless they putting somebody out of work.”

True Grits

Recently, I read in Yankee magazine that the Algonquin Indians of New England, not Southerners, invented grits. That may very well be true, but I don’t trust New Englanders — not even Rhode Islanders who make a corny cousin, johnny cakes — to cook grits.

Northerners just don’t get grits. In 1980, when I was living in Manhattan, I watched Stan Woodward’s hilarious and insightful documentary about grits on PBS’s WNET. Using a hand-held camera, the South Carolina filmmaker went from the streets of New York to the grist mills of the South asking people a simple question, “Do you eat grits?” A New York City construction worker replied, “Grits? Ain’t that the stuff on my collar?” New York Times food editor Craig Claiborne, who grew up in Indianola, Miss., replied by making a grits souffle.

True grits are cooked in the “grits belt” that stretches from Virginia to Texas. Kevin Whitener, who was our neighbor for nearly 30 years in The Plains, Va., and cooks at the Old Salem Cafe in nearby Marshall, makes the grits of my dreams.

Georgia is the middle hole of the grits belt: the one that’s comfy for someone with a grits belly. Grits became the state’s official prepared food in 2002.

Chris Smith, host of our Georgia trip, treated us to dinner at the Grits Cafe in Forsyth, near Macon. I ordered the fried catfish, remoulade and cheddar soft grits. I left the restaurant full as a tick.

High Sticking, Tripping and Roughing in Macon

I grew up in Massachusetts: a hotbed of ice hockey rest. So I just can’t get my head around professional ice hockey teams in the South. Sure, you can build a rink and import players from Boston. But how do you build a fan base in a region where people only like ice when it’s in Coke or sweet tea?

Yet there are five National Hockey League teams in the South. The Southern Professional Hockey League has 10 teams, including the Macon Mayhems, who were the 2017 President’s Cup champions.

Southern ice hockey teams have crazy good names, like the Roanoke Rail Yard Dawgs. But hands down, the best-ever professional hockey team name is the Macon Whoopees. The defunct team played in Southern Hockey League during 1973-74. A Macon reporter told me, “The first game the Whoopees played, folks left during halftime because they thought the game was over.” Poor attendance led the team to disband mid-season.

The Macon Whoopees rose again in 1996, renamed the Whoopee. After several owners endured seasons of poor attendance and financial losses, the team went belly up in 2001.

An East Coast Hockey League team, the Tallahassee Tiger Sharks, relocated to Macon in 2001. They became known as the Macon Whoopee and played just one season. The Macon Trax, a later effort to continue professional hockey in Macon, got stopped short.

I hope the Macon Mayhems, a relocation of the former Augusta River Hawks, will play in the city for a spell.

Linda Gasparello is co-host and producer of “White House Chronicle” on PBS. Her e-mail is lgasparello@kingpublishing.com

Follow

Follow

Leave a Reply