By Llewellyn King

The Vietnam War was much with me. I never made it to Vietnam during the war. But the war came to me in every job I had between 1961 and 1973.

It is not that I did not try to get to Vietnam as a correspondent, or even as a soldier. I registered for the draft when I arrived in the United States in 1963, but I was rejected because my eyesight was poor, I was married, and I was too old.

I started my long-distance association with the war when I was working for Independent Television News in London in 1961, and continued it when I moved over to the BBC. I was always selected as the writer for the Vietnam segments.

At The Herald Tribune in New York, on my first night, I was asked to pull all the files together for the lead story: Vietnam. Later at The Washington Daily News and The Washington Post, Vietnam always found me.

Now comes a novel and the war finds me again, as I read about correspondents David Halberstam and Peter Arnett; U.S. Ambassador Graham Martin, who was delusional about the situation; Nguyen Van Thieiu, the president of South Vietnam until his ouster. It is all as fresh as if it were the file coming off the teleprinter today.

The novel is “Escape from Saigon” and its authors, Michael Morris and Dick Pirozzolo, tell the last, desperate days of Saigon in 1975. It is a novel where the end is known, but not known; where the tension ratchets up each day of the countdown to evacuation on April 29.

In Washington, Congress had refused President Gerald Ford’s last attempt bolster aid to South Vietnam with a final $722 million. The major U.S. military participation ended with the peace treaty of 1973. For two years, the South Vietnamese had struggled on with U.S. support but without ground troops. The North Vietnamese would roundly violate the peace, and the South Vietnamese would live in hope that the United States would not let them be overrun. Forlorn hope.

The United States had lost interest in the war, after it had been so torn apart by it, and wanted no more part of a land war in Asia, or at that time, a land war anywhere. More than 50,000 Americans and an untold number of Vietnamese had perished.

Lessons? You draw them: secret plans, ground troops, aerial war, insuperable U.S. military might. These ideas are flying again about other regions of the world. Beware. Read this novel.

I have often thought that if the Kennedy brain trust had read “The Quiet American,” Graham Greene’s masterful novel about Vietnam, published in 1955, things would have turned out differently. We might have shunned involvement on the election of Jack Kennedy.

“Escape from Saigon” has the same ring of authenticity. It should: the authors both served in Vietnam. Morris was sent to Vietnam when he was just 19 years old and, as an infantry sergeant in Northern 1 Corps, he saw some of the fiercest fighting of the war. He was wounded and his bravery was rewarded with a Purple Heart.

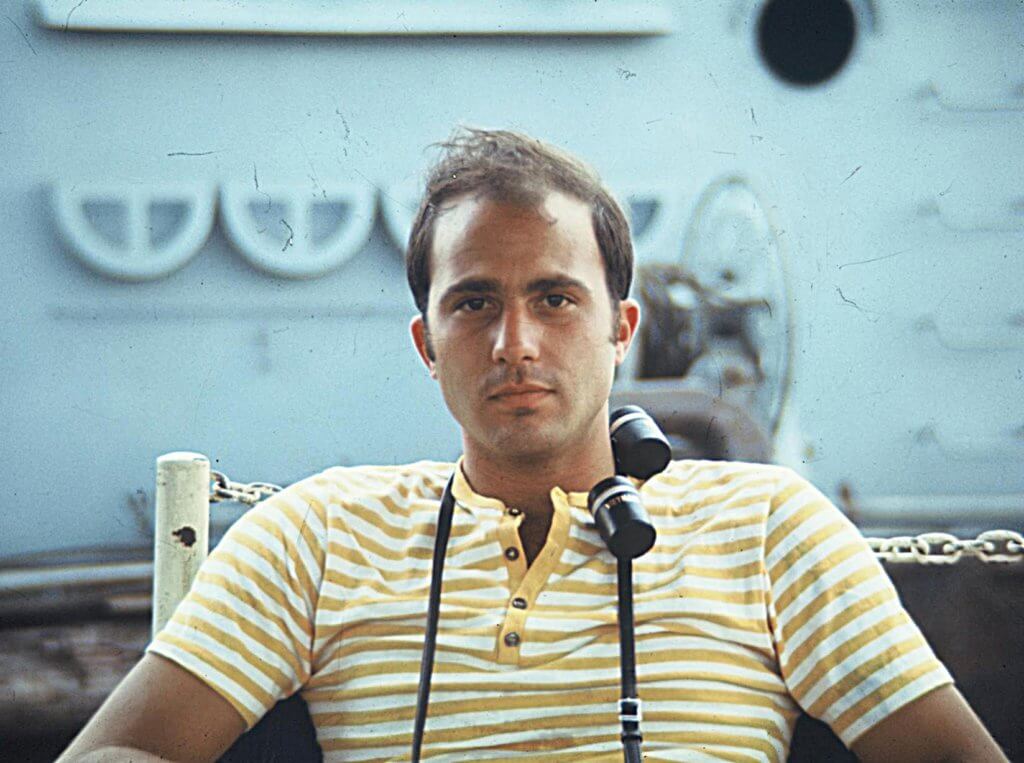

Dick Pirozzolo in civvies after a party trip on the Saigon River.

Pirozzolo was an Air Force information officer in Saigon. Perhaps that is why the city is so well described, from the watering holes to hotels, like the Caravelle and the Continental where so many journalists stayed and drank. Drinking was a part of Saigon in war.

When I finally made it to Vietnam in 1995, I traced the war from Hanoi, replete with its French boulevards down through Da Nang, Hue and China Beach. All so peaceful, after so much bloodshed. Battlefields are that way.

“Escape” could be a sad book, or a book of recrimination, or an attack on the American role. Instead, it is a novel of facts told through the lives of the people: journalists, a bar keeper, a priest, a CIA official, South Vietnamese who worked for the Americans and sometimes betrayed them, and those who fled by plane and boat.

The novel is exceptional in authenticity. Its portrait of city in extremis is chilling and completely engrossing. It will take many back and some forward — forward to new foreign involvements. — For InsideSources

Follow

Follow

Leave a Reply