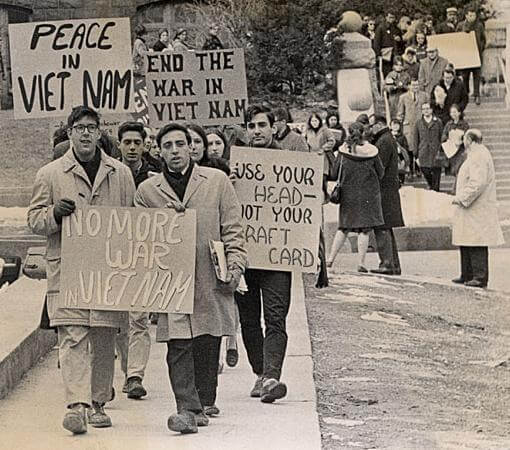

I remember the feeling in newsrooms back in the 1960s, as many journalists began to have doubts about the Vietnam War.

In those big workspaces where newspapers come together and broadcasts are assembled, the Vietnam War was taken by journalists to be the good guys versus the bad guys — the way it had been in the two world wars and the Korean War. But by the mid-1960s, the media was turning against the war.

Some reporters went to Vietnam, the rest of us edited and sometimes melded several files from the war.

Initially, coverage reflected simply what the U.S. commanders were saying in daily briefings from Saigon. As our colleagues on the ground in the war zone began to tell a different story from the official one, editors and writers far from Vietnam began to change their views. Enthusiasm turned to doubt, followed by anti-war sentiment. The media, in its way, had found its conscience.

Media doubt accelerated as the war dragged on and turned to something close to hostility. I was privy to this because I circulated as a desk editor between three newspapers: the Washington Daily News, the Washington Evening Star, and the Baltimore News-American, finally roosting at The Washington Post.

The American Newspaper Guild passed an anti-war resolution at its annual convention in Dallas in 1969. This side-taking disturbed many journalists. It wasn’t objective, but it passed anyway.

Today, the media landscape is different. There are many more partisan outlets in broadcasting and fewer strong, local newspapers. And there is the whole new world of social media, which defies monitoring. Still, the reporting is done by the mainstream media, and from this all else flows.

While the attitudes of the mainstream are important, they aren’t as commanding as they were in the time of the Vietnam War — in the time when the nation watched the evening news with total belief and hung on every word from Walter Cronkite.

I have a strong sense of that same struggle between the professional requirement for objectivity and the private conscience is testing the media today just as it did in the days of the Vietnam War.

Can we still cover the divisions of today as an event, as we do most things, or is it morally different?

There is an emerging consensus that journalists collectively — and a more disaggregated group couldn’t be imagined than the irregular army of nonconforming individualists who make up the Fourth Estate — are concerned about the survival of democracy. The very basis of our freedoms, of our pride, and even of our history as a free nation capable of the orderly and willing transfer of power is at stake. You can’t work in media now and not feel the sense of the nation going off the rails.

It is, I submit, a turning point when journalists of conscience can’t fall back on the old rules of objectivity, giving one opinion and countering it with another. To give the other side, when you, the writer, know the other side is a contrived lie, is to give credence to the lie and further extend its malicious purpose.

You can’t give the lie the same credence as the truth or you will hide in false equivalence and fail the public.

Even journalists I know who are socially and politically conservative are signing on to the idea that they must take a stand for the truth.

The Big Truth being that Joe Biden won the presidential election, verified over and over again by recounts and court findings. The false equivalence would be to repeat the Big Lie and say at the end of a report, “But supporters of Donald Trump assert the election was rigged.”

When you know that the future of our democracy is in the balance, as a journalist, you feel it is time to take a stand; not to stand with Democrats, but to stand with the truth.

Follow

Follow

I do agree, though reluctantly. Because I can see how the sacrosanct “objectivity” of the press has been misused. I’m not sure how to navigate the risky path between real objectivity and fake objectivity (as you describe), but I try to maintain a critical spirit/eye vis-a-vis all ideas. That is not objectivity, that is subjectivity, isn’t it, in the end. But otherwise there is no critical spirit, only a he-said, she-said sham democracy.