Innovation and entrepreneurism, these are strains of the American Dream. That dream is simple: to be self-employed, to own your own business, to be answerable to customers and not to bosses, as well as to make a better living and to enjoy the benefits of the tax system that favors business.

It may be fundamental to the dream, but students pouring out of universities are, by and large, unprepared to follow the business-of-their-own dream. We do not create in the educational system people equipped to launch companies that create jobs and protect the fabric of our society, giving it strength and texture.

At the base of the educational tower, students graduating from many high school systems are poorly equipped for little more demanding than fast-food service or day labor.

Graduates of liberal arts colleges have to seek jobs in large companies or in government. It is darn hard to start a history company or a sociology service, or to incorporate as a geography business.

In short, the liberal education system is skewed against entrepreneurship, particularly against small startups where sweat equity is the principal financing and where a single skill can be the foundation of a healthy enterprise.

I once heard a speech by one of the founders of Intel in which he said there was a difference between small business and new business. Quite.

It is small business that interests me. The little enterprises that are the essential ingredient in free enterprise, the source of creativity and, not to be forgotten, the source of happy and fulfilled lives. The pursuit of happiness can be entwined with the pursuit of self-employment in work that the worker loves.

When I first learned of a small college — minuscule, you might say, because there are fewer than 100 students — in Charleston, S.C., I was gladdened— and when I learned that about a third of its graduates had gone on to start their own small businesses, I was ecstatic.

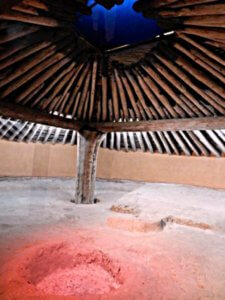

The institution is the American College of the Building Arts. Its mission is not to create entrepreneurs, but to meld together trade crafts and liberal arts.

Entrepreneurism is a byproduct, an unexpected bonus.

The combining of the liberal arts with skilled artistry is a potent concept at a time when there is an extreme shortage of craftsmen, and a real dearth of those who reach the master level, both men and women.

About a third of the student body at ACBA are women. In two days reporting at the college, I found women doing complex forgings in the blacksmithing department, chiseling stone in the masonry classes, and doing timber-frame construction.

The same students, away from the forges, chisels, hammers and saws are to be found studying Charles Dickens’ “Hard Times” and the Industrial Revolution or puzzling over Palladian concepts in the architectural drawing class.

If I sound enthusiastic about this concept in education, it is because I am.

My father was a blue-collar worker and small businessman, but he missed in his life, which was hard, the joy of literature, the stimulation of art and the wonder of the theater. He missed the liberal arts. For myself, I miss the satisfaction that he got from making a decorative gate in wrought iron or putting up a barn.

I find the idea the liberal arts can be taught alongside trade craft to be stimulating. ACBA President Colby Broadwater III, a retired three-star general, acknowledges the college is so small — it came out of a shortage of skilled artisans to do restoration after Charleston was hard hit by Hurricane Hugo in September 1989 —that it is less than a grain of dust in the stone carving room compared to big universities. But it is important, a frontier in education.

“Who said artisans shouldn’t be educated?” says Broadwater. Quite so.

I might add, “Who says they shouldn’t build craft skills into businesses?”

They are chiseling, hammering, plastering and sawing a new kind of educational future in a very small college.

Photo credit: Linda Gasparello